Intro

“It’s often said that if you really want to understand something, then build it. Take something like your own hand—do you really understand how it works? What it’s made of? How it functions? Well, one way to find out would be to make a machine…”

These are the opening lines to the documentary Automata, an engrossing film on machines called ‘automata’ in Far Western Europe.

Throughout history, engineers have studied the world by making machines to imitate it. The Wright brothers studied birds, while today’s robotics engineers study human behavior.

But before robots and AI and even planes, there were automata: beautiful machines that some now consider to be a “lost art.” Today, I will be attempting to detail the history of automata, their legacy, and impact on the world. Enjoy.

What Is An Automaton?

Firstly, let’s discuss what an automaton is.

An automaton (plural: automata) is a mechanical device that can perform a specific set of pre-programmed functions. Automata do not operate using electricity or sensors, and often require winding up. Many automata are powered by hydraulics for more complex movements. Automata generally resemble humans or animals, and are mainly for entertainment purposes.

Early History

Let’s play a game: Based on the definition above, when do you think automata were invented? The 1800s? 1700s? 1600s?

Try 400 BC.

Amazingly, the oldest documented automaton was a wooden, steam-powered pigeon, created by the Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum. (Unfortunately, we have no idea how this thing worked because no diagrams of the pigeon have survived.) In fact, the word automaton itself is Greek, deriving from the word ‘automatos’ meaning ‘self-moving.’

However, it is possible that automatons existed prior to the 400s BC. The Iliad—formally written between the 700s and 600s BC—described a series of golden maidens fashioned by the Hephaestus, the disabled god of craftsmen and metallurgy. These maidens helped the god in his forging work, and did a pretty good job of it, too. Hephaestus also invented a giant, boulder-slinging mech named Talos that guarded the shores of Crete.

Automata seemed to be commonplace in the Hellenistic World. At the Olympic games, an eagle and dolphin automata entertained crowds by flying and leaping through the air. Water clocks had singing mechanical birds. Human automata drank and served wine. In Rhodes, automata seemed to be as ubiquitous as modern billboard signs are to us.

But it wasn’t just the Greeks that were inventing automata. In the Han Dynasty (c. 200s BC), Chinese engineers fashioned an entire mechanical orchestra for the emperor. Others made mechanical horses and birds (the latter of which seems to be a favorite animal in the automata world).

Interestingly, the Chinese also had myths surrounding automata. In Liezi (c. 400 - 300 BC), a sassy triple-threat automata that could walk, pose, and sing performed for the King Mu of Zhou and his concubines. At the end of the performance, the automata winked at the king’s ladies and made “sundry advances” towards them. This offended the king, who promptly had the machine torn apart. (I’m not surprised...) News of this automata also gave two philosophers existential crises.

Mirroring the Liezi myth, most automata in reality were made for religious and/or entertainment purposes. However, there were a few automata that existed for reasons outside of wowing crowds.

Back in Greece, there was the Antikythera Mechanism, the world’s first mechanical calendar. The Mechanism was a complex cosmic calendar that contained information about and tracked various celestial cycles (e.g., lunar phases), planetary movements, and solar and lunar eclipses. This awe-inspiring creation was made somewhere between c. 200 BC and 100 BC, but unfortunately only survives in fragments.

As we can see, automata and machines as a whole were getting more and more complex throughout the civilized world. In the first century AD, Hero of Alexandria created a wide range of automata, including: a holy water vending machine (because, why not); a wind-powered pipe organ; and a fully automated puppet theater, whose dramatic performance ran almost ten minutes in length!

No original models of Hero’s automata have survived, though diagrams for his inventions have been reconstructed by other engineers throughout the ages. They’re impressive and detailed, which should be expected from the man who made the first steam engine!

Doubly unfortunate, though, is the fact that around 117 AD, somebody lost the instructions and engineers forgot how to make automata. Either that, of records on this era have simply been lost to time.

Obviously, I couldn’t readily accept this idea. So, I went deep diving on Google for any evidence for automata made between the 100 AD and 200 AD. I came up with absolutely nothing!

Even details on Chinese automata from this era are sparse. Chinese engineers continued to work on engineers from the 3rd century onward, creating water-powered puppet shows, musicians, and animals. However, diagrams and even paintings of automata don’t seem to exist.

By the Sui Dynasty (581-601), detailed depictions of automata reappeared. Automata were also apparently rather widespread by this point. Early hydraulics allowed for more complex and detailed machines. One grandiose display was the emperor’s 72 wine serving automata, which floated on a series of barges and served guests at every stop.

The Chinese took pride in their inventions and continued making automata through the Tang Dynasty. Impressive contraptions of the era included was an otter that caught fish, a monk imploring girls to sing, and a dragon that terrified the reigning emperor.

During the same era, Middle Eastern engineers got to work collecting Greek knowledge and applying it to their own works. Lions, singing birds, and automatic flute players entertained Byzantine nobility. The neighboring Islamic world had its own version of a mechanical orchestra, which could be programmed to play different pieces—arguably one of the first programmable computers.

Indians in the 11th century created human and humanoid automata that performed a wide variety of actions, ranging from fighting, to dancing, to…“love-making”…

While Chinese engineers grew disinterested in making automata during the 11th and 12th centuries, Western Europeans got a hold of this curious science. Europeans would usher in a new era, creating some of the most complex and stunning automata who would give performances to the fabulously wealthy.

European Automata

The Renaissance and the Enlightenment are eras I will never tire of discussing. Luckily, automata reigned during both of these intellectually stimulating periods.

In the 1200s & 1300s, ‘pleasure gardens’ for aristocrats were filled with automata—and rather mischievous ones at that. Automata in the Count of Artois’s gardens spat water at guests, spoke randomly, shot out flour and feathers, and even smacked guests in the head! But rich people like weird things like that, so it was funny.

Robert Bacon and Albertus Magnus were each said to have created a bronze talking head that could answer any question. (Both machines apparently were destroyed by people who didn’t like the answers given to them.)

The early Renaissance was an almost magical era for automata. Clock towers arrived in European cities, bringing iron roosters and dancing bears with them. In the 1490s, Da Vinci drew up plans for a mechanical knight.

As springs were perfected, they were paired with hydraulics and clockwork technology to create the next generation of automata. Mechanical angels graced churches, metal monsters spat fire, and clockwork lions flattered kings.

Automata continued to be a luxury enjoyed only by the wealthy nobility well into the Enlightenment era. These marvelous, gilded machines would not be seen by the masses until hundreds of years after their invention—if the machines survived.

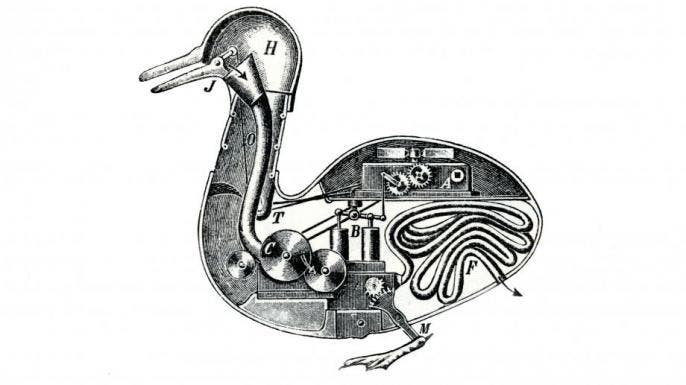

Many automata have been lost to time, including the impressive 1737 Flute Player. This machine was designed and built by Jacques de Vaucanson, during a time when we started to wonder if humans and machines aren’t so very different. Vaucanson built the Flute Player with pipes and valves resembling human wiring, and made the machine with a tongue and lips to be able to realistically play up to twelve individual pieces. This automata was also said to be covered with human skin.

Vaucanson also designed an equally impressive Drum Player and…a pooping duck. Unfortunately, the Flute Player, the Drum Player, and the Duck have all been lost to time.

The 1700s saw the rise of aggressive competition between automata engineers. And, as in any industry, competition drives innovation.

1768 saw the birth of The Writer—a two-foot-tall boy with over 6,000 parts that could be programmed to write any 40-character message. This marvel of engineering was created by Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a luxury watch maker. Jaquet-Droz, his son, and associate also worked together to create The Draughtsman—an automata though could draw detailed images, and The Musician—a breathing organ player.

All three automata remain fully operational today.

Perhaps the most beautiful automata I’ve seen yet is the 1773 Silver Swan, created by Joseph Cox (a jeweler) and John Joseph Merlin (creator of the roller skates). This jaw-dropping machine utilized clockwork motors to give movement to a life-size swan made entirely of silver. This swan preens its feathers and catches fish in a pool made entirely of swirling glass. Today, this work of art still performs for crowds at the Bowes Museum.

Cox also invented the Peacock Clock—a stunning automata featuring life-size, gilded models of a peacock, rooster, and owl.

The Turk

The world of automata wasn’t without controversy, however. One notable example was The Turk—a chess playing automata that could beat any player in the world. Introduced by Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1769, The Turk toured the world playing anyone who dared challenged him—and won. He had strategies and adapted as the game went on. He could even scatter pieces on the ground if someone tried to cheat!

For decades The Turk left everyone scratching their heads. Had machines really become conscious? Were we playing God?

Well…no.

In the mid-1800s, The Turk was caught in a fire, which burned through the machine and exposed its inner workings. Turns out, a human had to sit inside of The Turk for it to be fully operational. A skilled chess player (probably a child chess prodigy) would sit inside of a compartment where they could see the chess game as it was played. The player would then make their move and give the appropriate command to The Turk, who would then apply to move to the board above.

While not conscious, The Turk was still an interesting machine. Its functionality inspired the automatic loom, a machine that revolutionized the textile industry during the Industrial Revolution. It also inspired Charles Babbage, who would later create the first automatic calculator (i.e., the first official computer).

Modern Automata

The Industrial Revolution allowed automata to become more widespread and accessible to the middle class. Thanks to mass-manufacturing, people could now enjoy these marvels of art and science at parlors and even restaurants.

Interestingly, it’s only the 1860s to 1910s that are considered the “golden era” of automata. (“No one cares about your bourgeoisie swan, Merlin!”)

Perhaps this is due to the mass-production of such machines. Automata could be found everywhere from toy stores to circuses. Clowns were popular figures, as well as impish children, and animals lined with real fur. These automata focused on storytelling, displaying scenes of day-to-day life or even fantasy scenes of people from the far-flung East.

In Japan, automata served tea, while American ice cream parlors had coin-operated piano players. (Remember, during this time the Japanese were heavily influenced by the USA thanks to Commodore Perry inventing gunboat diplomacy.)

Even Thomas Edison created automata, such as a talking doll that recited “Jack and Jill.”

Unfortunately, many of these automata from the golden era haven’t been preserved as well as those from the 1700s. Perhaps it’s due to cheaper materials and/or poor storage conditions, but golden era automata seem more worn out than their predecessors.

Dawn of a New Era

So, what happened? Why don’t we see automata anymore?

One word: robots.

As the Industrial Revolution blazed new trails, electricity reinvented automata, allowing for “electric automata,” aka robots. Like the invention of steam power, hydraulics, and springs, electricity opened the floodgates to a new wave of creativity.

By the 1930s, stunning entertainment robots were performing for crowds. There was Eric, an “obedient” robot resembling a suit of armor. There was Electro, a smart-mouthed machine that loved smoking cigarettes (his companion was a dog named Sparko).

And outshining both was Alpha, a 6-foot tall, voice controlled robot. Interestingly, Alpha was an early source of robot panic. In 1932, Alpha shot his creator Harry May, leading newspapers to claim that robots would kill us all. While that never happened, over 90 years later, fear continues to surround robots and their A.I.-powered brains—a stark contrast from the religious uses of automata and the wonderment inspired by them.

As time went on, entertainment robots needed a new name. The Walt Disney company dubbed them “animatronics.” From the 1960s on, the Imagineers created a fleet of impressive machines, capturing every subject from singing birds, to presidents, to pirates. These animatronics helped to bring the parks to life, and continue to please crowds decades later.

Still to this day, Disney’s Imagineers continue to produce some of the most impressive animatronics in the industry, recently debuting their new A-1000 models for hyper-realistic movements.

Other companies would try their hand at animatronics, coming up with their own uses for robotic characters. This included terrifying generations of children via Halloween decorations and Chuck E. Cheese’s stage shows.

But it’s not just large corporations that are experimenting with animatronics. Indie projects like MaSiRo, a group of Victorian/anime-inspired waitresses, are finding new ways to bring novelty experiences to consumers.

Other companies are using AI to act as a brain for modern animatronics, giving characters more in-depth personalities and making them even more interesting to interact with. Ameca is currently one of the most realistic animatronics out there, while Eilik has found a place in consumer’s hearts with its charming personality.

Every year, new animatronics debut. This time, though, it is capitalism—rather than a king’s commission—driving innovation.

Conclusion

If jazz evolved into heavy metal, then automata have evolved into AI-powered androids that terrify the masses. However, like jazz, automata still exist today.

Toy makers and engineers continue to make automata that inspire and leave people curious to learn more. In fact, it was automata rather than robots that inspired me to pursue engineering. (I’m a sucker for ancient knowledge!)

There’s a certain sense of magic that’s inspired when we look at automata. It turns us into fascinated children, eager to pull the pieces apart and discover why a machine works the way it does. At the very least, we want to watch the performances again and again.

Automata are one of my favorite examples of when art and science collide. Throughout their history, they’ve prompted discussions on politics, nature, ethics, and what it means to be a human in this world.

Are we divine creatures or simply machines of flesh and blood? Can we create consciousness? Should we even try?

These questions remain unanswered and are still heavily debated in 2023. Perhaps we’ll one day answer these questions. Maybe we never will. Maybe we’re destined to keep reaching for an answer, only to blind-sighted at every turn by petty arguments and useless divisions that tear us apart.

What do you think?

What a cool article! The history of automata feels so uncanny, especially because it goes back so far into Antiquity. But it shows that humans have long experimented with robots and humanoid inventions.