OSOWEIC, POLAND — AUGUST 6, 1915 —

The sky was a murky violet hue as dawn broke over the marshlands. 7,000 Germans prepared to lay siege to Osoweic Fortress, a Russian stronghold they had failed to conquer twice during this brutal war. But as the saying goes, third time’s the charm.

At 0400 hours, the winds shifted in the German’s favor. Under the orders of Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, the soldiers released poison gas onto Osoweic. A fatal cloud of chlorine and bromine swept across the field, catching the Russian soldiers off-guard.

The surprise would make for an easy conquest, Hindenburg thought. But he and his men would find that they had severely underestimated the strength of their Russian enemies.

Osoweic Fortress, located in now-northeastern Poland, was a 19th-century stronghold to defend the Russian Empire from the rivaling Imperial Germany. Surrounded by marshlands, the strategically placed compound boasted a “multi-layered defense system”1 of trenches and high walls manned by shooters. Difficult to reach and even harder to penetrate, the Russians saw Osoweic as a reliable and effective fortress. To the Germans, it was a ‘bone in the throat’.2

Shortly after the Great War began, German forces learned of Osoweic’s effectiveness. In 1914, the fortress survived a six-day continual assault by the German’s large caliber artillery guns. When soldiers tried to attack the fortress head-on, were quickly felled by its Russian defenders.

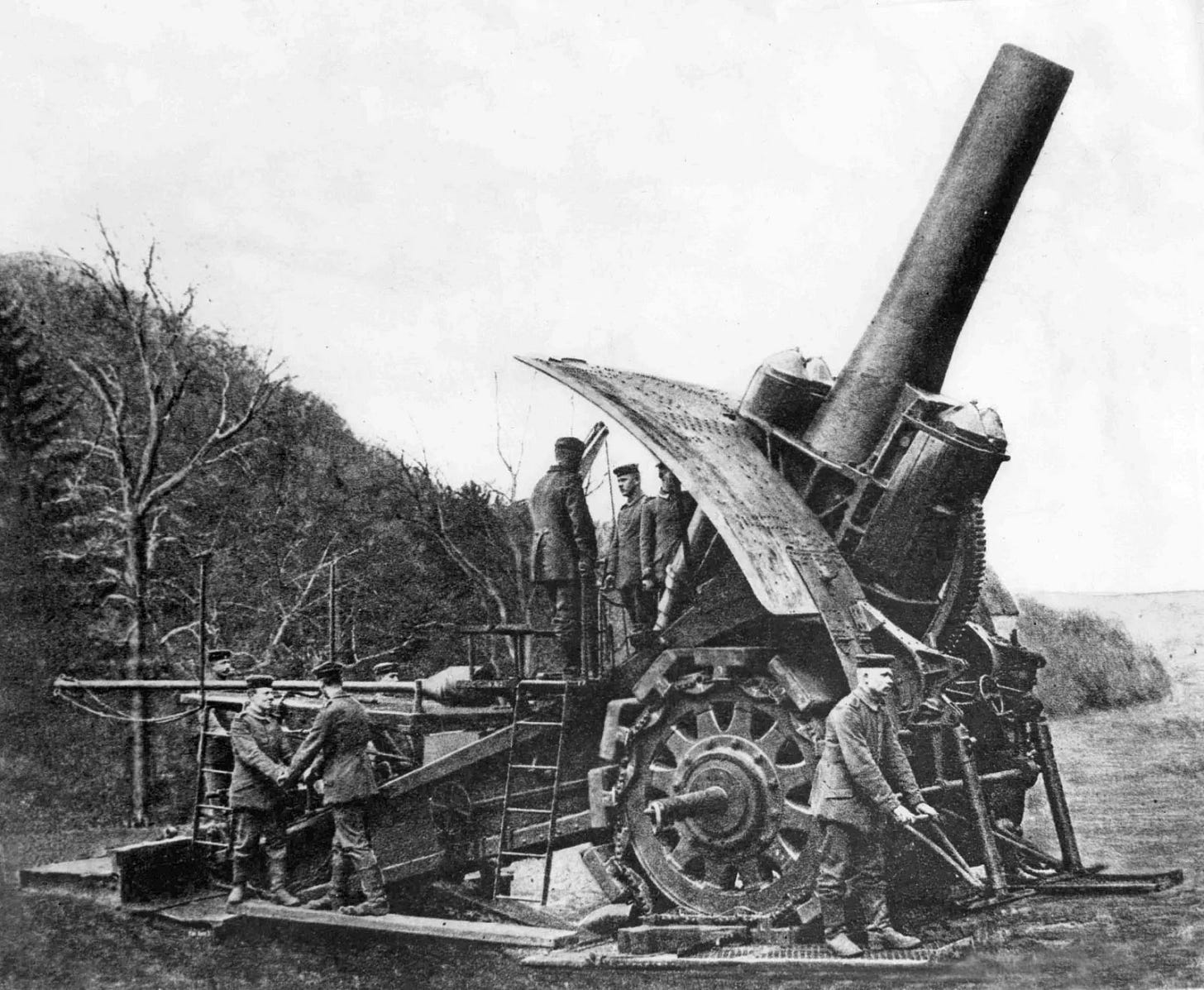

The Germans retreated shortly thereafter. But determined to conquer Osoweic, they attacked again in February 1915. Employing the use of Big Bertha cannons3—Howitzers capable of firing 420mm rounds at a distance of up to 9km4—as well as air bombings, Osoweic sustained heavy damage. Yet, neither Osoweic nor its men crumbled as predicted. The Russians defended their stronghold for several months before the Germans were forced to retreat once more.

After suffering defeat twice at Osoweic, German leadership began to grow frustrated. Securing the German-Russo border was vital to their efforts, and while Osoweic wasn’t a major stronghold, it wasn’t one the Germans could afford to ignore. Determined to succeed, the Imperial German Army called upon Paul von Hindenburg. Intimidating, blunt, and stern, Hindenburg was both a trusted officer and a highly respected figure in the public eye. Though he had initially retired in 1911 as a corps commander5, he dutifully returned to service in 1914 when the Great War began.

That same year, Hindenburg worked alongside Major General Erich Ludendorff6 to deliver a crushing defeat to the Russians in the Battle of Tannenburg. For his efforts, he was lauded as a hero and promoted to field marshal in late 1914. The German military leadership hoped he would repeat his success at Osoweic.

After making needed preparations, Hindenburg moved to attack in July 1915. With him were 7,000 soldiers, comprised of 14 infantry battalions and an engineering combat battalion, accompanied by 14 - 30 siege weapons.7 They outnumbered the Russians nearly 8:1.

Within the walls of Osoweic, the 900 of the Zemlyansky Regiment braced for attack as they watched the Germans nearing the imperial border. Trusting the fortress’s defenses, the men planned to defend Osoweic as they always had and force the Germans to retreat with their tails between their legs.

On July 24, the Germans began firing. The barrage lasted for over a week, with either side firing but never yielding. Amid the fighting, Osoweic sustained immense scarring, but the Germans failed to destroy it. Osoweic would survive battle once more, it seemed.

On August 5th, firing slowed to sporadic bursts as night fell over Osoweic. Russian guns eventually fell silent as the Zemlyansky Regiment went to sleep. A few select guards patrolled the fortress walls, whispering and laughing in the darkness as their cigarette flames burned against a blackened sky.

Across the marshland, the Germans prepared their next attack. Under lantern light, soldiers delicately arranged 30 batteries in a line. Each was filled with poison gas. A lethal mixture of chlorine and bromine, the gas was known for viciously tearing away men’s skin, leaving them with permanently disfigured bodies if the gas didn’t corrode their organs and suffocate them first.8

Since the 1800s, the use of poison gas in warfare had been recognized internationally as a war crime.9 10 Despite this, however, chemical weaponry was infamously employed over the course of the Great War. Imperial German forces used gases made of mustard, phosgene, and chlorine to wreak havoc on their enemies, as first seen in the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915, where over 1,100 men were killed from gas poisoning alone.

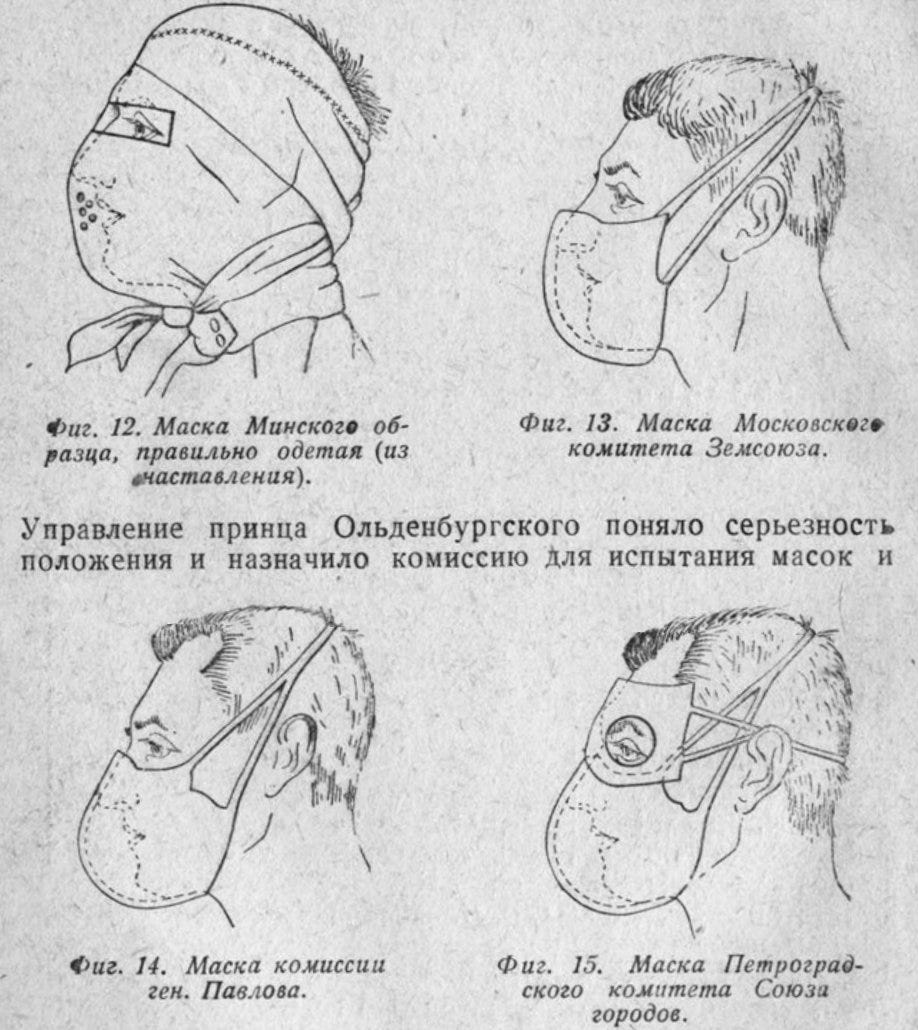

Russian soldiers were often easy targets for gas attacks. Though the imperial army had designed safety masks, they were poorly designed and not distributed evenly throughout the fronts. Further, for the Zemlyansky Regiment, Osoweic Fortress was not equipped to handle gas attacks.11 Without proper ventilation or protection, the men would die almost instantly.

At dawn, the 30 batteries were opened, releasing a formidable yellow-green cloud over Osoweic. Guided by the wind, the gas rapidly spread, altering everything in its path. One survivor stated:

“…the grass turned black, there were flower petals scattered everywhere…”

Caught in the apocalyptic haze, those outside the fortress were the first to die. Men collapsed, choking and gasping for breath in vain. Unable to scream, they would never be able to warn their brothers-in-arms that death had arrived. Once in the vents, the gas quickly flooded the fortress. Hundreds suffocated in their sleep. As the chemicals seeped into their skin, their bodies began to decay. Within minutes, their corpses became withered and corroded, with gaping holes in the place of flesh.

Lt. Vladimir Kotlinsky awoke in horror. Choking on blood, he found the world awash in a toxic lime haze. He stumbled from his rack to rouse the others, only to find mutilated corpses in almost every bed. Out of the 900 men who entered Osoweic, only 60 - 100 were still alive.

Realizing they’d been attacked, Kotlinsky took charge. Immediately, he ordered the others to cover their faces to prevent any inhalation they could. Scrambling, they took cloth from old rags and uniforms, doused them in urine, and tightly wrapped them around their faces. Kotlinsky guided his men through the gas-filled halls, though they stumbled, half-blind and spitting up chunks of their lungs. Kotlinsky himself found his skin had begun to deteriorate, leaving behind painful, bleeding wounds. Yet he and his men pressed on. Kotlinsky ordered his brothers-in-arms to grab their guns and gather outside. They obeyed.

Outside the fortress, Kotlinsky’s eyes burned as the wind blew gas into his eyes. Squinting through the haze, he saw the blackened field around him. He turned to his fellow soldiers, face wrenched with pain and fury. The young lieutenant could hardly stand, let alone speak. But no words were needed. The Germans had committed a grave offense against the Russian Empire, and they would pay for their crimes.

With their fading strength, the last men of the Zemlyansky Regiment gripped their bayonets and charged.

Across the field, the Germans began to march. Donned in leather gas masks, they stalked across the desolate marsh, trailing past Russian cannons caked in green oxide. It would be a smooth takeover, the Germans believed, with not a single bullet would fired that morning.

That was when the first man was killed. A bullet pierced through the haze and tore into his chest. The others stopped, eyes wide with confusion.

One of the soldiers whispered, “How…?”

Slowly, the fog parted. As the sun rose over Osoweic, an army of dead men came into view. Soaked in blood and bayonets gleaming, they staggered across the field, eyes burning with rage. Hindenburg’s men froze. Awestruck, they watched as the dead men aimed their rifles and opened fire.

When the reality of the situation hit the Germans, they fell into panic. Under the torrent of bullets, they dropped their guns and fled, howling in terror. In the madness, stampedes broke out. Soldiers trampled each other to death, while those who survived were ensnared in their own barbed wire.

Kotlinsky watched the chaos from afar. Coughing up another mouthful of blood, he gave the signal to his comrades. The guns of Osoweic fired one last time in a final deadly symphony. The horrified Germans were massacred within minutes, under heavy artillery and rifle fire; felled by the hands of the risen dead men.

The sun was high overhead once the surviving Germans had fled. The gas had cleared and the firing ceased. The corpses of German soldiers littered the fields of Osoweic.

It was done. The Russian Empire was safe for another day.

Lt. Kotlinsky shuddered. Beneath the warm, mid-summer sun, he collapsed. The gas had taken its toll and had destroyed his body from the inside-out. That night, he died at the age of 21 years old.12 For his bravery, he was posthumously awarded with the 4th Class of the Order of St. George. It is not known if and where he was buried.

Out of the 900 men who were tasked with defending Osoweic, less than a handful survived. Only one of the 8 high ranking officers survived, along with an additional 20 officers and 2 medical doctors. The remaining number of survivors is not known.13

Across the marsh, the surviving Germans retreated to safety, and Hindenburg lived to fight another day. He would survive the Great War, lauded and respected throughout Germany. He retired from the army once more in 1919, and became the second President of the Weimar Republic in 1925.

Inspiring, horrific, and beautifully tragic, the Attack of the Dead Men is a legendary story of loyalty and patriotism. The men of the Zemlyansky Regiment defended their empire to the very end, even as death held them in its grip. Charging with bleeding lungs, these men fought with untold bravery and won.

Reading about it over a century later, one wonders why they didn’t flee Osoweic. It would’ve been a rational choice. Charging was insane by comparison! But they didn’t flee. Instead, they picked up their guns and charged—out of dedication to their empire, its people, and each other. They valiantly defended the fortress and forced their enemies back once more.

Learning from the lessons of the battle, however, Russian forces would soon evacuate the fortress. Despite its men’s bravery—at Osoweic and beyond— Russia found it was largely ill-equipped for this new era of warfare. Osoweic was destroyed by the Russian Army two weeks later.

Throughout Europe, soldiers heard the legend of the army that rose from the dead to slaughter those who trespassed on their territory. The “Dead Men” of the Zemlyansky Regiment became one of the many strange and bizarre stories of the Great War, from Native Indian spirits saving their kin to angels patrolling the battlefield. Yet the Attack of the Dead Men wasn’t the result of superstition or some unexplainable event. It was the result of a few men’s unwavering duty and undying love.

Though once a popular legend, today, the memory of the Dead Men of the Zemlyansky Regiment has all but been forgotten. Even official data, such as the names and numbers of participants and survivors have been lost. Yet remaining fragments have been preserved by historians both amateur and professional, allowing the tale to live on. A few history-savvy entertainers have also paid homage to the battle, such as metal band Sabaton who in 2019, released an anthem to honor the memory of the dead men.

Though there is much to the battle that is unknown, the sacrifice and effects are clear to us. May the men of the Zemlyansky Regiment never be forgotten, though they forever rest enshrouded by mystery.

Beckett, J. (2024, January 13). Attack of the Dead Men: The World War I Battle That was like a scene out of a horror movie. Warhistoryonline. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/dead.html

Egorov, B. (2018, August 6). Attack of the dead: How fatally wounded Russian soldiers fought off a German offensive. Russia Beyond. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.rbth.com/history/328908-russian-attack-of-dead

Simple History. (2017, November 30). Attack of the Dead Men (Strange Stories) [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from [Link]

Romanych, M. (1998, July 20). Big Bertha | WWI German Siege Gun & Howitzer. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/technology/Big-Bertha-weapon

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Paul von Hindenburg. ushmm.org. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/paul-von-hindenburg

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Erich Ludendorff. ushmm.org. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/erich-ludendorff

Aguilar, S. L. C., & Caetano, I. M. (2023). Escrevendo história e identidade a partir da guerra: a Batalha de Osowiec na música e no cinema russo. Revista De História Regional, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.5212/rev.hist.reg.v.28.21961

Patton, J. (n.d.). Gas in the Great War. Retrieved June 12, 2024, from https://www.kumc.edu/school-of-medicine/academics/departments/history-and-philosophy-of-medicine/archives/wwi/essays/medicine/gas-in-the-great-war.html

ICRC Database (n.d.). Declaration (IV,2) concerning Asphyxiating Gases. The Hague, 29 July 1899., Retrieved June 12, 2024, from https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-decl-iv-2-1899

ICRC Database (n.d.) Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907., Retrieved June 12, 2024, from https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/hague-conv-iv-1907

Читать онлайн “Борьба за Осовец” - Хмельков Сергей Александрович - RuLit - Страница 23. (n.d.). https://www.rulit.me/books/borba-za-osovec-read-192413-23.html

Vladimir Karpovich Kotlinsky (1894-1915) - Find a. . . (n.d.). Retrieved June 13, 2024, from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/257853762/vladimir-karpovich-kotlinsky

It is possible that painter Władysław Strzemiński was a participant and survivor. Though he was in service at this time, this source seems to originate from Wikipedia and is not verifiable.

This dark age of warfare can't end soon enough.