“Look back over the past, with its changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the future.” — Marcus Aurelius

Over four thousand years ago, the first empire came into being under Sargon the Great of the Akkadians1. Since those ancient days, every era of our history has been marked by great empires and nations that have united, destroyed, and ultimately changed the lives of countless human beings. We look back—both fondly and bitterly—at our ancestors: the Persians, the Romans, the Mongols, the Greeks, and the many others who have changed the course of human history through war, creation, virtue, and sin.

Rarely, however, do we take the time to analyze why our predecessors are no longer around, or how we can learn from their mistakes. For those of us who do consult history, our search starts and ends with the Roman Empire. After a brief examination, we nod and say, “Yes, that’s exactly what’s going on in the West today.” Decadence, greed, complacency, and hyper-sexuality were indeed traits the Roman Empire had towards the end of its life, but these were also the same traits shared by every other great empire upon their decline.

One author who noticed this was Sir John Glubb, a British officer and scholar, whose admiration of history gave him insight on the lifecycle of all great empires and nations, and how the West is following the same destructive pattern. He published his findings in The Fate of Empires and The Search for Survival2 in 1978.

In this three-part series, we will be discussing this lifecycle, understanding how it relates to the dying American Empire, and whether it is possible to save it.

In this first part, we will discuss the ascent of great empires. Each empire is marked by three distinct eras: the Age of Pioneers, the Age of Conquests, and the Age of Commerce.

The Age of Pioneers

Energy, Passion, and Ambition

The Age of Pioneers is the dawn of a new era. Surrounded by dying empires, a new nation bursts onto the scene with patriotic zeal. This nation was once frowned upon by its peers as barbaric, chaotic, and disjointed. But now, this backward little nation is making everyone eat their words. What’s more is that this newcomer is often smaller, poorer, and outnumbered in every way possible. Yet through innovation and focus, the ambitious underdog successfully dominates the reigning superpowers. The young nation conquers lands and acquires wealth along the way, successfully turning it into an empire.

A few examples of nations that survived and surpassed this stage include the Macedonian, Turkish, Mongolian, British, and Spanish empires.

The United States itself checked all the boxes of an underdog nation before the Revolution of 1776. Disjointed colonies? Check. Large swathes of uninhabited territory? Check. Weird language mechanics? Yep. Ambitious and aggressive? You bet.

Like the young USA, nations during the Age of Pioneers have specific key traits. The people—specifically leaders—are ambitious, brave, courageous, determined, innovative, and proactive. Their focus is to make their burgeoning society victorious on all fronts. Patriotism is present in a pure and raw form, making the intelligent and hungry underdogs a force to be reckoned with.

Lacking capital and rigid traditions the people of newborn empires are more resourceful than later generations. People experiment to find the best solutions. When applied to the battlefield, this allows young armies to slaughter legions of their enemies with great efficiency.

This is in direct contrast to the nation’s enemies—the old, dying empires. These superpowers are characterized by wealth, opulence, and passive complacency. In 1776, British authors scoffed at the notion of the thirteen colonies becoming independent. In An Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress (1776)3, John Lind arrogantly wrote:

“The opinions of the modern Americans on Government, like those of their good ancestors on witchcraft, would be too ridiculous to deserve any notice…”

Lind then goes on to moan about how the Americans had no right to speak of “grievances,” believing that Parliament and the King’s actions towards the colonies (i.e., unfair taxation, blockades, etc.) were sound. Declaring independence was a foolish mistake. Obviously, Lind was totally right! Like, literally, the British decimated—Wait, what’s that? They lost?!

Oh…

See, kids? Arrogance gets you nowhere fast.

Why the underdog nation wants to make a name for themselves varies widely, and must be viewed in the context of the specific nation’s history. However, common reasons include: desiring the wealth of another nation; aspiring to emulate a long-gone culture; being attacked by outsiders; or being fed up with tyranny.

Men of new empires, often young and rowdy, fight with passion to overthrow their enemies. Often outnumbered in every way, the desire for a new way of life drives the young empire until it finally usurps the authority of its older foes. The nation’s victory acts as a source of inspiration throughout the civilized world, with the people in other, often older nations quickly emulating the young empire’s characteristics. The Revolution of 1776 sparked similar movements throughout the Western world, with the most notable example being the French Revolution of 1789.

After claiming victory over their enemies, the new empire must find structure. At the end of this Age, laws are implemented and borders secured. However, the young nation remains restless. The people remember their recent victories in battle and crave more. They are swept up by the idea that it is their divine right to expand their empire. In fact, glory has already been pre-ordained. When this idea becomes fashionable, so thus begins the Age of Conquests.

The Age of Conquests

Glory, Honor, Unity

Welcome to the “glory days.” Energized by their victories and craving more, the young empire rushes forth to explore, conquer, and settle new lands. Large swathes of foreign territory are quickly acquired, both by military force and voluntary association.

This era is marked by great pride in the military. Duty and sacrifice are the highest of all virtues. Glory and honor are “the principal objects of ambition.”

For the United States, we call this era Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion. The Louisiana Purchase, War of 1812, Mexican-American War, Alaska Purchase, and other such events allowed the young empire to grow into a formidably sized nation, spanning the width of an entire continent and beyond. Guam, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, Alaska, Hawaii, and swathes of Mexico were placed under the American Empire between the early 1800s to the 1890s.*

*It is worth noting that the length of every Age varies per empire, but the general pattern still stands. Overall, the average empire lasts 250 years. (More on that later.)

The end result of this Age is that one, large nation is formed. This nation—as mentioned previously—must be maintained by unifying laws or risk dissolution. The United States fought to stay unified as new territories were acquired and questions of proper governance arose. This, of course, led to our Civil War—a common event for many empires at some point or another. While many empires have fallen apart over civil wars, the American empire was able to maintain itself and reunify. Shortly thereafter, it was able to continue its rapid expansion and development of previously settled areas.

During the Age of Conquests, commerce is promoted almost by default. The reason is that the conquest of foreign lands means new resources—new ideas, natural resources, etc. Unified under the same banner, language, and laws, the people from the original lands of the empire begin to trade with those living in newly acquired territories. As ideas are shared, experimentation and innovation abound, ushering in the next era: the Age of Commerce.

The Age of Commerce

Duty, Innovation, Wealth

The Age of Commerce often overlaps the Age of Conquest, as imperial expansion gives way to economic prosperity and a flurry of new market opportunities. For example, the annexation of Hawaii occurred in 1898, coinciding with America’s Age of Commerce.

Glubb stated that the Age of Commerce occurs naturally, even amongst “savage and militaristic empires…whether or not they intend to do so.” With a rapidly expanding empire, a new range of climates and resources are acquired, allowing for the production of a wide range of products that are desired both throughout the empire and the wider civilized world.

There is a level of prosperity encouraged by having many lands unified under a single entity. People trust one another more when they know they are doing business with a fellow countryman (an ally until proven otherwise), more so than when doing business with a foreigner (a potential foe). This trust among citizens is crucial to the empire because it is still fairly young, and foreign allies could turn into enemies if given the chance. The citizens are quick to trust their own, though this can easily turn into xenophobia through misguidance.*

*During this Age, immigrants are more willing to assimilate than they during the later stages of the empire. This aids in their economic well-being, allowing them to be trusted more by the hesitant, natural-born population.

During the Age of Commerce, military traditions still hold sway. Boys are raised in intentionally rough conditions, with schools intending to produce “a strong, hard and fearless breed of men.” In wider society, people are still very patriotic and find pride in courage, duty, and innovation. Honesty is deeply valued, as people understand that all markets are founded upon trust. Conversely, lying is viewed as cowardice.

As the Age progresses, these traditions and values gradually give way to the desire to earn wealth. (Glory and honor, while dandy, don’t always add to the bottom line.) Enterprising citizens form partnerships, start businesses, and form new vehicles for generating and maintaining wealth (e.g., patents, trusts, etc.). Technologies are both invented and reinvented, with the main intention to be sold as commercial products and/or services.

Thanks to the wealth earned from Commerce & Conquest™, Glubb states that the middle and upper classes grow “immensely rich.” Saddled with this newfound wealth, people of the Age of Commerce begin to spend their fortunes on the arts, sciences, and a myriad of luxury goods.

Through donations, commissions, and organizations, city streets become lined with beautiful, if not, grandiose architecture. These buildings flaunt the prowess of the empire, with the intent to inspire awe and pride in those who see them. Examples of such buildings include the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (once the largest church in the world), and the Woolworth Building in New York City (once the tallest building in the world). Other investments during this Age may include roads, bridges, communication systems, museums, theaters, and libraries, depending on available technologies of the day and the empire’s unique culture.

For the United States, the Age of Commerce ran from the 1870s to the 1910s—also known as the Gilded Age.

High Noon

Start of the End

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end. Every empire must have its High Noon. During this stage, the immense wealth and prosperity of the empire “dazzles the onlookers.” Foreigners long to live in the reigning nation, while those within it slowly grow arrogant, bitter, and complacent. Virtues such as courage and patriotism decline, but remain just high enough to help the empire defend itself.

Greed and hedonism are the driving forces behind an empire’s decline. During the High Noon, the nation becomes reactionary—it wants to retain its wealth and luxury, rather than innovate and expand. Many empires make the foolish mistake of becoming isolationists.

In wider society, military aggression is frowned upon. Empires are inherently evil. Imperialism brings no positives. The nation’s history becomes a source of shame for the people. To cope, the people say they are, in fact, morally superior to their forefathers. Passivity is a virtue and demilitarization is an honorable act. In Glubb’s words:

“This intellectual device enables us to suppress our feeling of inferiority when we read of the heroism of our ancestors, and then ruefully contemplate our position today. ‘It is not that we are afraid to fight,’ we say, ‘but we should consider it immoral.”

Such behavior ultimately spells disaster for a nation. When faced with the threat of invasion, the increasingly lazy empire makes foolish decisions. During modern France’s High Noon, the government came up with the amazing idea of the Maginot Line. The world stood back and watched as the Germans quite literally went around it, making the Maginot Line less effective than a wall of LEGO bricks. France suffered an embarrassing defeat, being conquered in little more than a month4.

A government’s duty is to protect its people. The French government failed to protect its citizens. But the government didn’t do it because they were seduced by the ideals of pacifism. Rather, when governments pass such policies, they do it out of “selfishness, and the desire for wealth and ease.” When a government has a “weaken[ed] sense of duty,” their people suffer.

Prominent rulers of High Noon stages include—but are not limited to—Caesar Augustus, Sulaiman the Magnificent, Queen Victoria, and Woodrow Wilson.

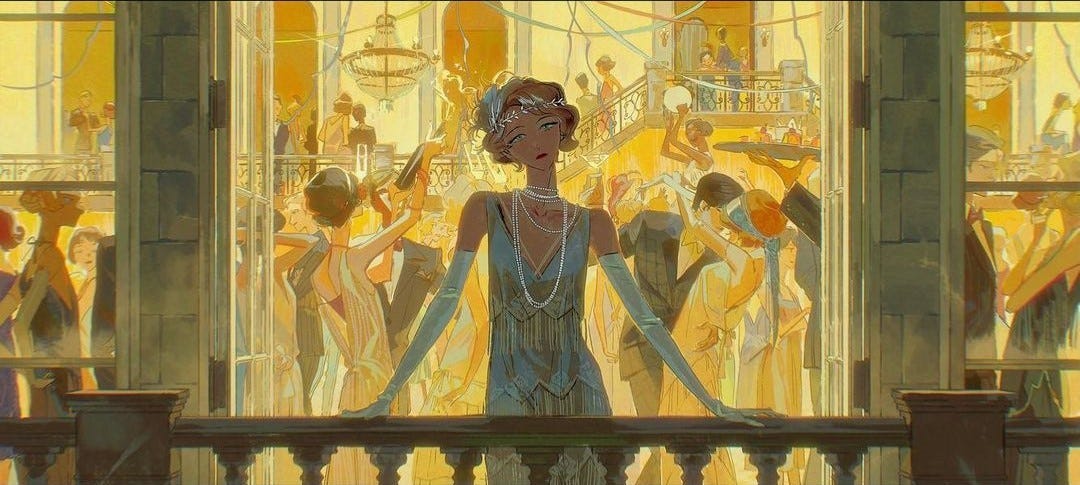

Glubb proclaimed that America’s High Noon was during Wilson’s presidency (1913 - 1921). However, given that WWI was in full swing during most of Wilson’s presidency, we will say that America’s High Noon was in the 1920s.

One can easily understand why we turned to pacifism after the Great War—millions of lives had been lost, uprooted, and forever changed by the horrific events sparked by one of the world’s most influential assassinations. Though, when viewed through the lens of the imperial lifecycle, we can see that this was not the wisest decision. America’s increasingly popular ideals of pacifism, complacency, and greed marked the start of the end.

To be continued…

Dalley, S. M. (1998, July 20). Sargon | History, Accomplishments, Facts, & Definition. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sargon

Glubb, J. B. (1978). The Fate of Empires and Search for Survival.

Lind, J. (1776). An Answer To The Declaration Of The American Congress.

Battle of France | History, summary, maps, & Combatants. (2019, May 10). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved September 7, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-France-World-War-II/The-fall-of-France-June-5-25-1940

I’m so glad I found your Substack. I read too much history to disagree with anything you say.

Greed and hedonism; that says it all.